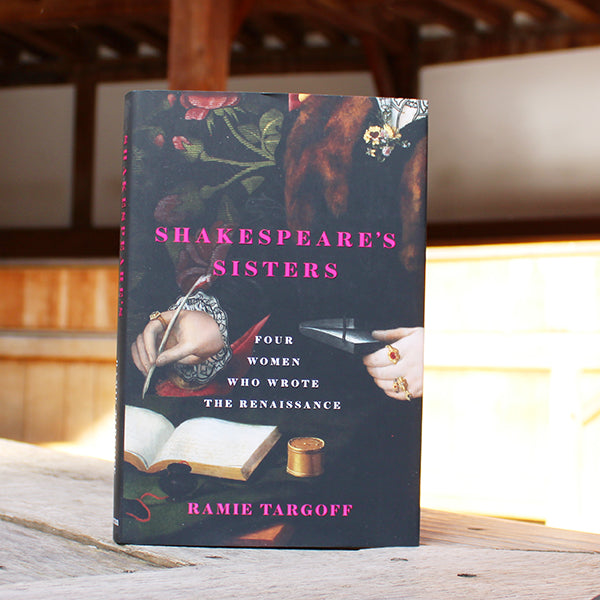

Ramie Targoff’s Shakespeare’s Sisters responds to a provocation from Virginia Woolf’s seminal essay, A Room of One’s Own – if Shakespeare were to have a sister endowed with equal talent, her literary undertakings would have been rapidly quashed by the restrictive, patriarchal circumstances of the time. Woolf’s rendering of Jacobean England does not see writing as a viable profession or hobby for women, as writers such as Mary Sidney, Elizabeth Cary, Aemilia Lanyer, and Anne Clifford remained largely out of her purview. If she were to read Targoff’s Shakespeare’s Sisters, she would have been enlivened by the stories of these women and how, amidst the political and religious tumult of the 17th century, they could establish and assert their identity through the written word.

Targoff opens the book with a play-by-play of Queen Elizabeth I’s funeral, which allows her to start etching the connections between these women. These connections gradually form an intricate nexus. Targoff’s chronological approach allows us to see how Sidney, Cary, Lanyer, and Clifford and their struggles do not exist in isolation. She is keen to establish the interconnectivity of their lives and literary practice through her chronology rather than examine each writer separately. Whilst some readers may not favour such an approach, preferring instead to read about a singular writer before moving on to the next, I find merit in Targoff’s choice, as she deftly examines the different stages of each woman’s life within the broader historical context that informs their actions. Rather than have Shakespeare’s Sisters begin and end at the four writers’ literary careers or examine them in relation to the men in their lives, Targoff’s holistic approach, tracing their lives from childhood to death, offers the reader valuable insight into the various influences Sidney, Cary, Lanyer, and Clifford were contending with throughout their lives.

The incredible scholarly undertaking to piece such a book together is continually made apparent by the ease with which Targoff parses the social, cultural, and political lives of these women into a compelling narrative that keeps us connected to them and the core issues they were battling, is incredibly commendable, as it makes for a deeply engaging read, particularly for those who do not reach for history books very often. Targoff enriches her account with references to a myriad of biographers, historians, and even the jottings of Aemilia Lanyer’s astrologer, proffering a wealth of notes and further reading for the reader to engage within their own time to further investigate and delve deeper into the histories of these women. By contextualising these women within the legal matrices they were forced to navigate with difficulties by virtue of their sex, such as Clifford’s lifelong inheritance battle or Lanyer’s petitions at the Chancery court, Targoff foregrounds these women as powerful agents of their own lives, even when contending with constrictive conditions of their lives, and a society that sought to subdue them and relegate them to society’s periphery, through means of legal, religious, and financial desolation.

In the penultimate chapter, Targoff reflects on Cary’s writing – ‘“But to be quoted in the margin”: what better description could there be of women’s role in history?’ However, it is safe to say that Targoff, through Shakespeare’s Sisters,’ has successfully drawn these women from the marginalia to the main page.

Reviewed by Mahvish Malik (Education Administrator)