William Shakespeare didn’t just shape English literature — he was a linguistic trailblazer! The Bard coined or popularised an estimated 1,700 words and countless phrases, and his influence still echoes in our daily conversations. While Shakespeare was able to conjure pathos, poetry and hilarity with a turn of phrase, some of his contributions to the English language are a little… odd. Surprisingly, these off-the-wall expressions have survived for over 400 years, and we often don’t even realise that we are quoting Shakespeare.

Let’s explore a few curious phrases we owe to the Bard of Avon — and what they originally meant.

“It’s Greek to me”

“Those that understood him smiled at one another and shook their heads; but for mine own part, it was Greek to me.”

Spoken by Casca Act 1 of Julius Caesar

When we say something “is Greek to me,” we mean we don’t understand it. This one was literally about not understanding a foreign language. In Julius Caesar, Casca uses it to mock Cicero's speech, which he didn’t understand because it was in Greek.

“In a pickle”

“How camest thou in this pickle?”

Spoken by King Alonso in Act 5 of The Tempest

Today, if you’re “in a pickle,” you’re in a tight or troublesome situation. In The Tempest, the phrase is used to mean someone in a confused or drunken state.

“Wild-goose chase”

“Nay, if thy wits run the wild-goose chase…”

Spoken by Mercutio in Act 2 of Romeo & Juliet

A wild goose chase today means a futile or hopeless pursuit. But originally, it referred to a type of horse race where riders followed a lead rider at set distances — like geese flying in formation. Shakespeare transformed it into a metaphor for chasing something unreachable – well, knock me down with a feather! (not Shakespeare…)

“Knock knock! Who’s there?”

“Knock, knock! Who’s there, i’ the name of Beelzebub?”

Spoken by Porter in Act 2 of Macbeth

While Shakespeare didn't invent the concept of a knock-knock joke, his use of the phrase in the Scottish play is considered the first known instance of it in literature. In Macbeth, a drunken porter stumbles to the gate and acts as a “porter of hell,” knocking and responding to imaginary callers.

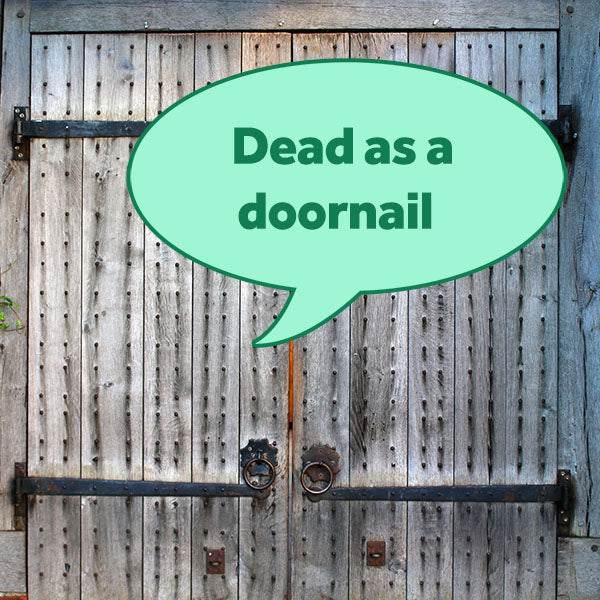

“As dead as a doornail”

“Look on me well: I have eat no meat these five days; yet, come thou and thy five men, and if I do not leave you all as dead as a doornail, I pray God I may never eat grass more.”

Spoken by Jack Cade in Act 4 of Henry IV, part 2

This is a very odd one! Maybe Shakespeare just liked the alliteration of dead and doornail? As Charles Dickins muses in A Christmas Carol, there is nothing particularly dead about a doornail.

Mind! I don’t mean to say that I know, of my own knowledge, what there is particularly dead about a doornail. I might have been inclined, myself, to regard a coffin nail as the deadest piece of ironmongery in the trade. But the wisdom of our ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the country’s done for. You will therefore permit me to repeat, and emphatically, that Marley was as dead as a doornail.

In Shakespeare’s day handmade nails would have been a valuable commodity and would often have been reused. In building doors, however, nails were ‘dead nailed’, the nail would be driven right through the door and bent over into a staple. We see this on the doors to the Globe Theatre.

“Break the ice”

“If it be so, sir, that you are the man must stead us all, and me amongst the rest, whose wooing shall be thus much for my part, sure I shall break the ice…”

Spoken by Tranio in Act 1 of The Taming of the Shrew

How many of us have recoiled in dread when an ‘icebreaker’ is mooted during a team meeting? In The Taming of the Shrew, it’s about getting past social stiffness — melting the metaphorical frost to allow a relationship to begin.

“Without rhyme or reason”

“Was there ever any man thus beaten out of season, when in the why and the wherefore is neither rhyme nor reason?”

Spoken by Dromio in Act 2 of The Comedy of Errors

This saying describes something which makes no sense either logically or poetically. The linking of these two alliterative nouns is at least as old as the poet John Skelton, who in the 1520s wrote that "For reason can I none find/ Nor good rhyme in your matter." The phrase as we use it today, however, is first recorded in Shakespeare's earliest comedy.

Many of these phrases may sound peculiar or even nonsensical out of context, but they’ve managed to survive centuries and become part of the English language’s rich collection of strange everyday phrases. So the next time you're “in a pickle” or trying to “break the ice” at a party, thank William Shakespeare!

![Out, Out Brief [Playhouse] Candle Stubs!](http://shop.shakespearesglobe.com/cdn/shop/products/swpcandles.jpg?v=1722516059&width=200)